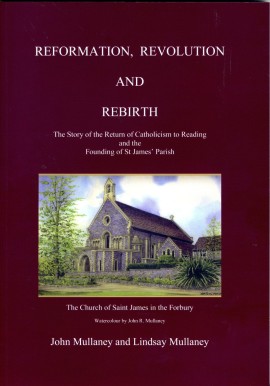

Reformation, Revolution and Rebirth ISBN 978-0-9572772-0-5

The Story of the Return of Catholicism to Reading and the Founding of St James’ Parish. £10.00 PLUS £2.80 P&P

Our researches uncovered many documents never previously seen. We also gathered a wealth of material which we couldn't fit into the book. We decided at the time of writing that once we had a website and had published the book we would make this available.

You will find here transcriptions and translations of many of these documents and in some cases copies of the originals. Where relevant we have given chapter and page references to the book. We hope this will increase your enjoyment of the work.

We had to make a choice as to the starting point of the book. To begin in the late 18th century with an account about the return of Catholicism at this time would have meant making massive assuptions about the background knowledge of our readers. So we decided to show how and why there were so few Catholics in and around Reading in the 1790s. This meant going back to the beginning of the penal, anti-Catholic laws at the time of Elizabeth 1. The other problem was whether to go even further back in time and describe the growth of Reading and of its Abbey from the 11th century.

Since there are so many outstanding works already available on this subject and Reading Museum is a centre of excellence on this topic, we decided this would be superfluous and we could only cover it in a superficial manner. Even one extra chapter would also increase the cost of printing the book and add little to the understanding of how, when, where and why St James' Church came to be built.

TO ORDER Please email jgmullaney@aol.com

The Chapter headings below are taken from the book to give the reader an idea of its contents.

CONTENTS

SECTION A

REFORMATION AND REVOLUTION

PART 1

The National and International Background to the

Return of Catholicism to Reading

CHAPTER 1 Page 7

Historical Background: Introduction – Catholicism, The Protestant Succession and The Religious Question.

CHAPTER 2 Page 10

The Penal Laws in the Eighteenth Century: Enforcement – The International and National Situation: Legislation – The 1559 Elizabethan Oath – The 1774 Oath – War – The First Catholic Relief Act, 1778 – The Gordon Riots, 1780 – The Debate within Catholicism in England – The 1791 Catholic Relief Act

.

PART 2

The Return of Catholicism to Reading, 1790 – 1817

CHAPTER 1 Page 20

Catholicism in Reading and the Surrounding Area in the Late 18th Century: Franciscans at Whiteknights – Reading and the 1791 Relief Act – Reading Town and Anna Maria Smart.

CHAPTER 2 Page 25

The Reading Mercury: Smart and Cowslade, Publishers and Printers – The Cowslade Family, 1783 - 1811 – Marianne Smart and Elizabeth Lenoir – Francis Cowslade: Joint Proprietor 1811 – 1834, Editor 1830 – 1834.

CHAPTER 3 Page 32

The First Mass Centres in Reading since the Reformation: Minster Street Mission Chapel, 1789 – Finch's Buildings; The Mission Chapel, Hosier Lane, 1791 – 1811.

PART 3

The French Revolution and Reading

CHAPTER 1 Page 37

Revolution in France, 1789 - 1793: The Revolution as Reported by The Reading Mercury – The Revolution and the Church – The Civil Constitution of the Clergy – War and the Execution of the King, 1792 - 1793.

CHAPTER 2 Page 45

The Exodus of the Clergy: England and the Emigré Clergy – Reactions to the Arrival of the Exiled French Clergy, 1792 – 1796.

CHAPTER 3 Page 50

The French Priests in Reading 1796 - 1802: Arrival In Reading – Life in the Reading House – Return to France, 1802.

SECTION B

REBIRTH

PART 1

The Life of François Longuet and His Work in Reading

CHAPTER 1 Page 57

The Young François Longuet: The Early Life of François Longuet – First Years in Reading, 1802 - 1808.

CHAPTER 2 Page 60

The Longuet - Poynter Correspondence and Plans for a Chapel: Proposals for a New Chapel - The Chapel of the Resurrection – The Dispute between Longuet and the Smart Sisters.

CHAPTER 3 Page 72

The Opening of the Chapel, 1811 – 1812: The Chapel, the House and its Furnishings – Life at the Chapel of the Resurrection.

CHAPTER4 Page 81

Longuet’s Death and its Aftermath: Longuet’s Murder – The Aftermath and the Disposal of Longuet’s Property – Longuet’s Legacy.

PART 2

CRISIS YEARS AND READING’S FIRST ENGLISH PRIEST

SINCE THE REFORMATION

CHAPTER 1 Page 93

1817 – 1820, Crisis Years: Introduction – The Missionary Colleges, The English College, Douai – Catholic Education in England during Penal Times, Twyford and Old Hall Green – The Reverend Mr Francis Bowland.

CHAPTER 2 Page 97

Catholic Emancipation, 1829: Background – The Gandolphy Affair and the Quarantotti Rescript – The 1805 Bill and its Aftermath – Reading in 1820.

PART 3

SAINT JAMES’ CHURCH

CHAPTER 1 Page 103

The Wheble Family and the Building of St. James’ Church: The Wheble Family – Abbé Pierre Louis Guy Miard de la Blardière – The Abbey Ruins and James Wheble – The First ‘Parish Priest’ of St James’ Church.

CHAPTER 2 Page 112

Pugin’s First Church Design - The Building and Opening of St James’ Church: Laying the Foundation Stone, 1837 – Pugin and the Norman Romanesque Style – The Official Opening of St James’, 1840.

PART 4

PUGIN AND THE DESIGN OF THE CHURCH

CHAPTER 1 Page 119

The Question about the Original Design: The Abbey Ruins – The Norman-Romanesque Style.

CHAPTER 2 Page 122

The True Principles and their Application to St James’ Church: The Principles of Architecture – Columns and Buttresses – The West Front – Pinnacles – The Roof – Gables – The East End – Mouldings – Mouldings and the West Door – The Windows – The Metalwork – The Woodwork – Conclusion.

POSTSCRIPT Page 147

The Abbey Ruins and the Forbury after 1841.

The Abbey Ruins and Reading Today.

APPENDICES Page 149

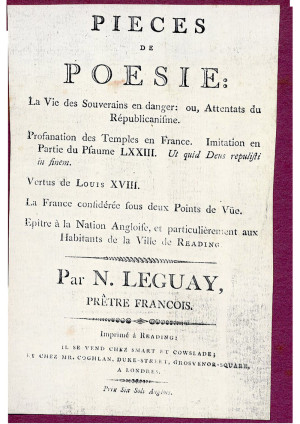

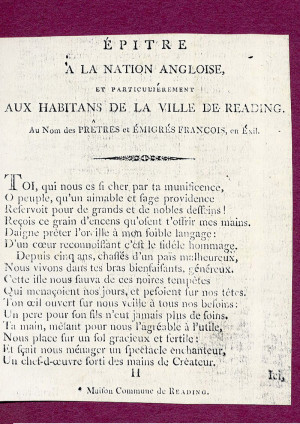

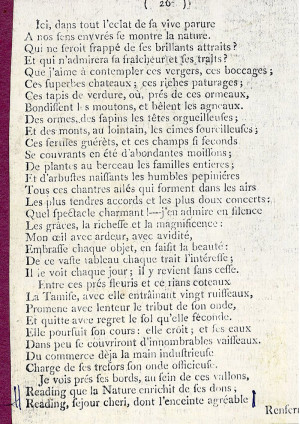

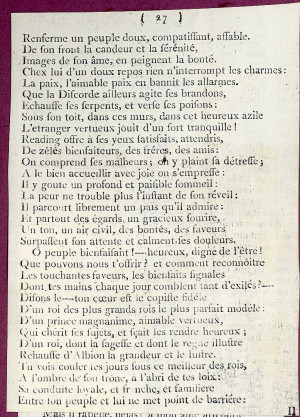

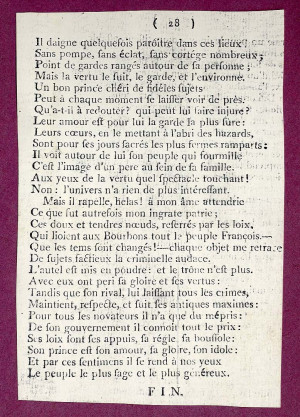

A. Letter to the English People: A poem by N. Leguay, a French Priest.

B. Obituary of Anna Maria Smart.

C. Catalogue of Longuet’s Books at the House in Vastern Lane.

D. The Consecration of St. James’ Church at Reading, The Tablet, August 1840.

E. Pugin’s Letter to Father Ringrose, August 1840

.

F. St James’ Archive Group.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SOURCES Page 156

THE AUTHORS AND OTHER CONTRIBUTORS Page 158

*******************************************************************

ERRATA

To err is to be human. We feared that as soon as we opened the returned printed copy we would spot mistakes and indeed this proved to be the case. Some are typos, others more serious. We shall try to put these right here and on the website, as and when we or our readers spot them. Do contact us if you find any errors.

1. The first mistake we saw was on page iii under Acknowledgments. We must apologise for not spotting that we misspelt David and Mary Langshaw's name. It is printed as Langford. We feel terrible about this, especially as they had been so kind as to invite us to their house. This is the Castle Street House where the émigré French priests lodged from 1796 to 1802. It is also one of the most historic houses in Reading and it was a great privilege to see around it. So our apologies go to Mary and David.

2. Somehow part of a paragraph was omitted in the final submission to the printers. The error is at the foot of page 58. The paragraph should read:

A letter from Mr (we would now call him Father), Webster, the priest at Woolhampton, to Bishop Poynter in March 1817, after Longuet’s death, gives us an interesting picture of how the

Catholic community in Reading was served by both

local and French clergy at the time of Longuet’s arrival. Father Webster’s style is verbose and his use of punctuation sparse. However it is worth struggling through his long sentences to get a hint

of annoyance at the young priest ‘muscling in’ on his territory.

3. Page 105. The caption refers to the house with the ‘blue door’. This was printed before we realised we would not have colour pictures on this page. The house is in fact the large four storey one second from end of the terrace. See photo below.

4. Page 124. The caption to the picture should read Fig 2.

5. Page 73 The date in paragraph 3 shoudl read Feb 13 1817 not 1812

*******************************************************************

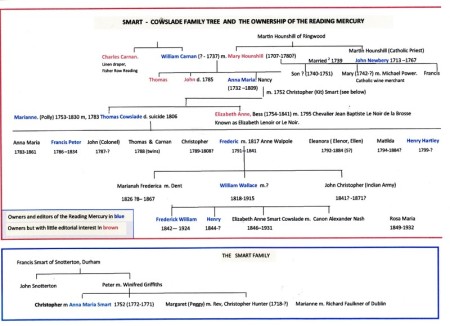

FAMILY TREES

Part of our researches included tracing the family trees of the Whebles and Smart/Cowslades. I am putting some preliminary results on the website but I have a great deal more detailed information which I shall be adding, so please keep referring back to the website.

It might help to print these lists off whilst reading the book, or at least to have them on screen for reference. I hope this will be useful whilst reading the book to identify some of the main characters. One of the problems is that the same first names recur over several generations. These tables should help identify individuals. In the case of the Wheble family I have typed the main James of each generation in orange.

WHEBLE FAMILY TREE

Robert James (dates to follow)

James (1729-1801) m Jane Eyre (1750-1839)

James 1779-1840 married 1 1802, Maria Talbot (1780-1814)

married 2 1815 or '16 Maria O’Brien (1788-1834)

CHILDREN OF JAMES AND MARIA TALBOT

1 Maria Joanna 1803-?: 2. Frances Margaret 1805 -1824: 3. Elizabeth Maria 1808-1812 :4. Lucy Catherine 1809-?: 5. Charlotte Anne 1812-1827

CHILDREN OF JAMES AND MARIA O’BRIEN

1.Maria Juliana 1816-1832: 2. James Joseph 1817-1884: 3. Edmund Joseph 1813-?: 4. Maria Theresa 1820-1824: 5.Robert 1821-?: 6.George Vincent 1822-1832: 7. William Francis 1823-?: 8. John Jospeh 1824-1854 m Catherine Elizabeth daughter of 3rd Earl of Howarth: 9. Daniel O’Connell 1829-?:

SOME BIOGRPAHICAL NOTES

Maria Talbot was a niece of the 14th Earl of Shrewsbury

RECORD OF DEATHS. Taken from the Woodley Registers (Scantlebury)

1814 25TH January: Maria Talbot buried in Winchester Catholic cemetery

1824 4th June: Frances Margaret ditto

1824 same day : Maria Theresa ditto These two children died together in a fire.

1826 24th January: Elizabeth Maria Buried in Bristol

1827 7th June: Caharlotte Anne Buried in Witham , Essex

1832 15 October: George Vincent Buried in the New Parish Cemetery, Hampstead, Middx.

1832 9th October: Maria Juliana Buried in the Winchester Catholic Cemetery

1834 9th July: Maria O’Brien (2nd wife of James)

Died in London. Buried in Winchester Catholic Cemetery

1839 5th September: Jane Eyre (Mother of James). According to Scantlebury died at Woodley.

1840 20th July: James Buried in Winchester Catholic Cemetery

********************************************************************************

Reading Museum has three early photographs of Helen, Matilda and Henry Cowslade dated in the 1880s.

The French Priest’s Poem

See page 48 and Appendix A Page 149 in the book.

This is an extraordinary document which gives us some idea of the gratitude felt by the French émigré priests for the welcome they received in Reading. It is one of a number of poems in a book entitled Pièces de Poésie.

Unfortunately the book itself has disappeared but we owe the survival of this particular poem to Eric Stanford. He is a noted sculptor, (his Spanish Civil war monument is outside Reading’s Civic Centre), and was also a curator at Reading Museum for many years. Eric and his wife Helen lived in the house in Castle Hill where the French priests were housed. He very kindly loaned us his notes for a history of the house and also a scrapbook which included photocopies of the poem. The French version below is reproduced from this scrapbook. Note the archaic French spelling and grammar.

The author is given as N. Leguay. His name does not appear on the list of émigré priests, compiled from many sources, in Bellenger’s book The French Exiled Clergy, though two other Leguays are listed. This is one of many mysteries about the priests that remain to be solved. We are still hoping to trace a copy of the complete book, which was published, as might be expected, by Smart and Cowslade. The Bodleian and British Libraries do not hold copies and the Reading copy is no longer in the Library. It was probably lost or taken from the shelves many years ago. We should be most grateful if anyone knows where we can find a copy.

The original is written in very florid Alexandrines, the heroic poetic metre used by Corneille and Racine, the great French dramatists. In translating the poem, it seemed appropriate to use Iambic Pentameter, the classic English poetic form used by Wordsworth who was writing in England at the same time. I have attempted to reproduce the highly emotional tone of the original while remaining as true as possible to the content.

It has been suggested, perhaps unkindly, that Monsieur Leguay never visited Reading, so fanciful are some of the descriptions of the landscape, particularly the frowning mountain peaks in the distance. However, other aspects do ring true and we know from other sources that the house on Castle Hill was, at the time, on the fringes of a countryside rich in meadows, woods and market gardens. It is also fascinating to read the description of all the mercantile traffic on the Thames as England’s industrial revolution led to greater foreign trade.

Politically, the poem makes very interesting reading. The author is clearly a great admirer of George III, who had supported the émigré clergy both by allowing his palace in Winchester to be used and by sanctioning the King’s Letter, the national appeal for the benefit of the priests, which raised the enormous sum of over £41, 000, four times the expected amount. This was despite considerable suspicion towards the French priests by many sections of the population, who regarded them with grave suspicions both because of their ‘Popish’religion and as potential French spies. Further evidence of the Reading community’s gratitude toward s George is provided by the wording surrounding the flowerbeds of the parterre in front of the house, as described in Chapter 3 of the book.

Documents, pictures and sources

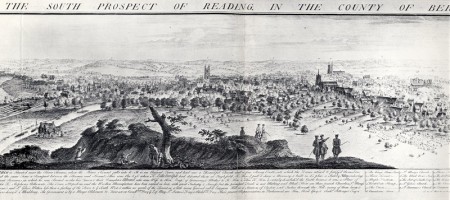

The above is an 18th century engraving of Reading. It has extra relevance to our work as it shows the main 'houses' mentioned in the text. The first of these is the Kings Arms or Castle Hill House where the majority of French priests lodged from 1784 to 1802. Almost behind it is Finch's Buildings desribed in Part 2 Chapter 3.

THE COWSLADE MANUSCRIPT

Typed by Lindsay Mullaney in November 2011 from the handwritten transcription by Archbishop King.

According to Christopher Devlin in his book Poor Kit Smart, the original was destroyed in a bombing raid during the Second World War. This has been confirmed by Portsmouth Diocese arhivists. The Cowslade manuscript is widely quoted throughout the book. It is not only a vital source of contemporary and near contemporary information but makes interesting and often poignant reading.

For this reason we have decided to make it available in its entirety. The following is how it appears verbatim in the book held by Portsmouth diocese as copied

out by Father (later Archbishop) King

Reminiscences – Traditional and Personal – of the Reading Mission from 1752* to 1840 by an Old Catholic (Miss Cowslade.)

(Copied from a MS in the Reading Mission Box, at Bishop’s House, Portsmouth.)

In the year 1752 (* cf COMMENT at end) my Grandmother, Anne Maria Smart, was sent to Reading by her relations to take the management of the then sole County newspaper, the long-established ‘Reading Mercury’. She was the widow of the unfortunate poet, Christopher Smart, well known to the chief literary men of the period. On her own side, she was the descendant of a respectable Catholic ancestry and like her progenitors adhered to the Faith through all the obloquy and insult attached, at that time and long after, to its name and exercise.

In defiance of the reproachful words of her Protestant patrons, Mrs Smart sent her daughters Marianne and Elizabeth to the Ursuline convent at Boulogne-sur-Mer, where they remained three years. In this asylum of innocence and peace was laid the solid groundwork of religion which endured through all the moral trials, hardly conceivable in these less ignorant and therefore less bigoted days, which beset their early youth. These first impressions lasted to the end of their career, as did their filial love for their first holy teachers.

When my grandmother first came to Reading there was but one (known) Catholic in the town, an elderly lady named Flowers, who, by some lucky oversight in the management, had been admitted as an inmate in a Protestant Almshouse. There was then no place of Catholic Worship within reach except the mansion in Whiteknights Park, two miles distant, then the seat of Sir Henry Englefield, and Mapledurham, the estate of the Blount family. Each of these establishments had a private Chapel and resident Chaplain. There Mrs Smart and her daughters had the privilege of attending Divine Service on the appointed days. The Rev. G. Baynham had charge of the Mission at Ufton Court, that estate then belonging to the Perkin’s family, passing by heirship to Mr Jones of Llanarth who continued to support the mission though not residing on the estate. Mr Baynham, who had been a student and received Holy Orders at Douai, numbered among his flock at Ufton, the Hydes of Hyde End (a small estate three miles distant) and some of the surrounding farmers and peasantry, whose humble modes of conveyance were, during the service, in waiting in the Court yard. Ufton Court was an ancient Catholic mansion, where, though the building is now parcelled out into cottages, is still shewn the underground room called the ‘Priests’ Hiding Place’ in which, in times of persecution, a priest, at the peril of his life could occasionally, offer the Holy Sacrifice and administer the Sacraments to such Catholics as could attend by stealth. At long intervals Mr. Baynham would go to Reading to give the Sacraments to the Catholics there, now increased in number, though not improved in position.

Mrs Smart had rented a room in Minster Street, of which a side door opened into a yard; through this private ingress the members of the small Congregation reached their obscure place of Worship. One eventful morning the youngest (sic) Miss Smart entered this alley at an earlier time than usual, intending to prepare for Holy Communion, when she was abruptly stopped by the master of the house saying to her ‘ You cannot perform here this morning’. Recovering from her surprise she answered ‘Why not?’. He rejoined: ‘Because my wife is in child birth and she cannot be delivered while you are performing.’ To this Miss Smart made no other reply than by lifting the latch of the Chapel door, on which the landlord exclaimed in a threatening tone: ‘If you attempt to perform, I will disturb you.’ Miss Smart, while her heart was dying within her, answered resolutely: ‘Do so at your peril’. Renewing his threat, the man retired. The service began and went on without interruption beyond the sound of vessels being emptied with the accompaniment of offensive smells which passed for accidental with all the Congregation but one, who, as soon as the service was over proceeded to carry into effect the plan she had formed in the course of it. At the western end of the town was a block of respectable houses known as Finch’s Buildings, each of which had a garden in front for vegetables and fruit. One of these being vacant, Miss Smart took upon herself to secure it on the strength of a small legacy lately bequeathed to her by a relation. Through the medium of a correspondent she sent a proposition to some Emigré priests then at Dover (awaiting the directions of the English Government) to come to Reading and occupy the humble abode she had prepared for them. In the evening of a wintry day, four of these reverend Exiles presented themselves at the Office of the Reading Mercury in lay costume of no very recherché make or material, and described by the chief official there, as looking like ‘a party of smugglers’. They knew no English and the daughters of Mrs Smart, with some trouble, revived enough of their long disused Convent French to make themselves understood by the Exiles, the youngest of whom (Abbé la Blardière), hearing the words ‘Comment vous portez-vous?’, threw up his arms, uttering an exclamation of joy. Under cover of the evening – to avoid the more than probability of insult - Miss Smart conducted the reverend strangers through bye-ways to the abode she had secured and furnished for them by means of the legacy alluded to. An airy room on the second floor was subsequently fitted up as a Chapel: the requisites being supplied chiefly from Whiteknights, whence the Englefield family had removed in disgust at the offensive prejudices of the neighbouring Gentry.

When all was ready, notice was sent by the new residents to a dignitary of their former diocese, who was styled Monsieur le Doyen, who came at their invitation to join their small community and whom I, (a child at the time), remember as the personification of priestly dignity. On being introduced to his humble abode, he expressed pleasure, exclaiming ‘le joli petit presbytère’. As time went on changes ensued. The Dean and the priests who had followed him to Reading were sent to their destinations and of the occupants of Finch’s buildings, five only remained – three of whom augmented the slender Government allowance by teaching French in the schools of the town. For many years the Catholic members of my family attended Divine Service in this ‘stable of Bethlehem’, with small increase of congregation and no decrease of popular prejudice. The services in Latin, and the absence of dignity in

the exercise of the Ritual, increased the scorn and aversion which, by the lower orders was insultingly manifested, and ill concealed by the higher.

In process of time, a considerable number of the Emigré Priests were sent to Reading by the Government and established in a large quadrangular building in an airy and elevated part of the town, once an hotel and still bearing the name of the King’s Arms, affording, from the size of the rooms, an abode less unworthy of its destination than the obscure tenement in Hosier’s Lane.

Memory can still take me back to my first attendance at the service in the King’s Arms, where, from my seat I watched the priests as they entered the Chapel, each with a book in his hand and a low wooden stool under his arm. One of them ascended the pulpit and gave the signal of preparation by a sonorous blow of his nose, thus awakening a chorus long and loud which was renewed at certain pauses in the sermon, the preacher each time giving the note to this, to me, extraordinary performance. After the sermon Benediction was given from the Altar which, with its wax tapers, the real labour of the bees, and profusion of flowers (justly called artificial) presented to me a grand spectacle, and I remember a feeling of surprise on being commended as a good little girl for having been quiet and orderly during the long service.

These reverend Exiles were in the sequel removed to various localities, carrying with them the revival of the Faith so long lost or buried, in the Land which had received and maintained them. While in Reading they led a monastic life only leaving their cloister for a daily ramble in the then quiet and rural glades in their vicinity: walks which my Aunt’s hereditary Muse has commemorated in some elegiac lines beginning:-

Yes, ye neglected shades, ‘twas here awhile

The peaceful tenants of yon neighb’ring pile

Were wont to seek the solace of their woe,

Or brood their sorrows, silent, sad and slow,

Here fell the tears to their lost country given,

Here sighs of meek devotion rose to Heaven.

The four priests who remained in Finch’s Buildings continued there for some years carrying on as well as they could in that ‘Upper Chamber’, with its adjoining narrow closet for a sacristy. The senior priest l’Abbé Godequin acquired enough of English to hear confessions and attend the sick, till a change ensued in the small community by the addition of the young priest François Longuet, who, by dint of personal privations and teaching French in the town and neighbourhood, and in process of time, stored up a sum sufficient to enable him to commence and eventually accomplish his long projected design of building a Chapel on a piece of land at the rear of the Grammar School, then conducted by Dr. Valpy. This undertaking was completed, and the little edifice (to which the Founder had given the name of the ‘Resurrection Chapel’) consecrated by the Rt. Rev. Dr Poynter in 1812, and attended by a congregation increased in number, though not in wealth or influence. The position of Catholics in Reading at that time was not a character to invite settlers. No tradesman could carry on his business in a town and neighbourhood where others of his own Faith could not, and the divergent Sects would not, or in many cases dared not, support him. The most efficient portion of the little flock were travelling Italians carrying good on their own account or as agents for houses of business. The names of Borelli, Gatti, Cerighetti and Primavesi are in honour with the remaining old Catholics as earnest and practical supporters of their Faith and its appointed Pastor.

From this period nothing worthy of note occurred in the annals of the Reading Mission till the tragic event which took place in February 1817, abruptly closing the career of its zealous and hard-working minister and spreading a feeling of consternation not only in his own Flock but to a wide extent in the provinces. About twelve months preceding this event the Abbé Longuet had been visited by a most painful illness from which it was not expected he would recover: but on its taking a favourable turn, he said to his venerable confrère the Abbé Godequin, ‘ Since I am not to die of this illness, I foresee my fate. I shall die a violent death, as several of my family have done, the last being my father who was guillotined.

As soon as his health was sufficiently restored he resumed his occupation of teaching French and Latin to the sons of respectable people in the village of Pangbourne. In the evening of Feb. 13th, having received the half-yearly payment owing to him, he took his leave and mounted the pony which was brought to the gate. The mistress of the house held a light and remarking the unusual darkness of the sky, urged him earnestly to dismount and pass the night under her roof: but assuring her that he had not the slightest apprehension, he bade her farewell and rode off at a brisk trot. Early in the morning he was seen by the village postman lying in the middle of the road, in a pool of blood, lifeless and shewing evidence of having been dead several hours. The news was carried to his residence by persons who had found his pony quietly grazing in a bye-lane. After the inquest, which gave no clue towards discovering the perpetrators of the murder, but showed that a sharp instrument had been used by a gash across the forehead which the cut hands had been thrown up to protect, the body was borne to the house in Vastern Lane and placed in the sanctuary of the Chapel where the members of the congregation assembled to weep and pray. The coffin was uncovered and the members were permitted to breathe their requiem and shed their tears over his bier. The mortal remains of the Founder were deposited under the sanctuary of his chapel and after a lapse of 23 years removed to the crypt at the Church of St James. The impression of horror attending this event continued to be renewed long after the occurrence by the persistent investigation of circumstances and the prolonged enquiries which were assisted even by the Government. The strange circumstance of the sum of money received by Mr Longuet on the night of the murder, being taken, while his watch was left, suggested the suspicion that the murderer was no stranger, and was, it might be, cognizant of the remittance of £25 received by Mr Longuet on the night of the dark deed. This latent suspicion glanced towards a youth, the son of respectable parents, but known to be of irregular habits, and addicted to gambling, and it was subsequently strengthened by the departure of the father and his family from their long established residence in Reading.

For three ensuing years, the Reading Mission had no appointed minister. Two of the aged residents of Finch’s Buildings officiated in Vastern Lane on the Sundays and Festivals, and the Rev….. Webster from Woolhampton came at Indulgence times to hear confessions. The venerable Abbé Godequin did not long continue in his share of these labours. One Sunday morning on my way to Vastern Street I met him slowly wending his way towards the Chapel, painfully dragging his legs which were frightfully swollen with dropsy. Repelling my expressions of concern, he bade me hasten to the Chapel where he was to officiate for the last time. He secluded himself from all but priestly intercourse weeks before he was called to depart with the ‘Sign of faith’ and sleep the ‘Sleep of peace’.

His confrère and constant companion, the Abbé Gondré, had taken his share in this portion of the vineyard. Sturdy of frame and ascetic in habits, he was well fitted for the labour assigned to him: to say Mass in the neighbouring localities, to which he usually went on foot, no priest or chapel being within reach of the scattered Catholics. In his character the Abbé Gondré exhibited a remarkable combination of the serpent and the dove. A child in worldly matters, he was a sound theologian, whom his elders in age and in the ministry would consult on difficult points, always accepting his elucidation. This adherence even to the letter of Scripture, the following instance will show. Being told of a man who had been beating his wife he exclaimed in genuine astonishment: ‘Il est donc fou! Le mari et la femme cela ne fait qu’une chair. S’est-il jamais vu qu’un homme batte sa propre chair?’

His abstemious habits and frugal mode of life, together with occasional remuneration for his priestly services enabled him by slow degrees to carry into execution a work he had much at heart, a translation of Duquêsne’s Evangile Médité. This project, with the money he had stored up for its execution he confided to my aunt, with the express condition that the work should be gratuitous and of wide circulation. Through unnumbered obstacles attendant in those times on employing a Catholic Publisher, my aunt was able to accomplish the work and its condition: the residue of the copies went to Australia with Bishop Polding.

The next incident in the history of the Reading Mission was the sudden announcement that the Rev. Francis Bowland had been appointed to take charge of it, and was waiting at Stonor Park till the house in Vastern Lane could be got ready for him. The news was received with joy, and the new Incumbent was welcomed by the heads of his congregation to the ministry which he carried on with little change or event for many years: the only occurrence claiming notice during that period being the nomination of Mr Wheble of Woodley Lodge (since restored to its original name of Bulmershe Court), to the office of High Sheriff of the County and his, so to speak, triumphal entrance into the town on the first day of the Assizes with an escort of Gentry and Yeomanry unprecedented in number and importance on any former occasion. The Catholic Sheriff, loyal to his Faith, and outspoken in its profession, went in his carriage with his domestic Chaplain by his side and his retinue preceding and following him, to the obscure Lane and humble Chapel which had never till then witnessed such a gathering. The Catholics in the town then first began ‘to hold up their diminished heads’.

Mr. Bowland carried on his ministry to the year 1837. After working successfully in raising contributions to the contemplated Church of St James, finding he was not to be appointed to it, he retired from his position and was succeeded by Rev. Moltene. (sic Molteno) The health of this young priest failing after a comparatively short ministry, he was replaced by Rev…. Harris and finally by Dr. Rock.

It had been the fixed intention of Mr Wheble, when the church which he had founded and was then erecting should be completed, to obtain the appointment of the above-mentioned distinguished ecclesiastic to its ministry. But Dr. Rock was resolute in his refusal and the unlooked for disappointment conveyed a shock to Mr Wheble, which, suffering as he then was from disease of the heart, was thought to be the immediate cause of his sudden death. A calamity so unexpected was not only a personal grief but for a time a crushing blow to the Catholics of Reading, aware more or less of the vexatious obstacles and delays which had prolonged the erection of the new building. The eyes which had looked up with grateful joy to the walls rising from the scattered flints of the ruined Abbey were now cast down in dejection and doubt. He, whose position and influence had been the rallying point was now taken from them and there was a latent misgiving if, or when, these old-new walls would be consecrated.

Mr Wheble had determined that the new church should be opened on the ensuing 5th of August, the Feast of the B. Virgin ad nives: he had given orders for inscriptions on some memorial brasses to be placed in the church and he directed that a tablet should be affixed to the Baptismal Font, recording that the new Church of St James ‘was opened’ on the above mentioned day. Comments, especially painful to Catholics’ ears were consequent upon this premature inscription. But it was executed to the letter, by the Bishop and Clergy of the Diocese, who, with closed doors, consecrated the building on that day.

Shortly after, the Rev. John Ringrose was appointed to the Mission and commenced his ministry under difficulties which his forbearing and conciliatory disposition was peculiarly fitted to deal with, till by degrees the insulting prejudices of all ranks in a town which swarmed with Dissenters, gave way to time and to the endurance of the truly Christian minister.

-----------------------------

Wide and long as is the space upon which I have thus looked back, to me it is brief when measured with the changes it comprises.

Catholic children can now go to their own Church or school without being hooted by a youthful rabble: their elders can frequent a public Library without encountering an insult or a lie in every book they open whether for information or amusement: can see their grand Ritual carried out with fitting solemnity in a majestic sanctuary and listen to Divine lessons from appointed teachers while strangers come no longer to ‘scoff’, although they may not always ‘remain to pray’.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Note 1. The Abbé Blardière was educated and ordained at Rouen, where his uncle was a Canon of the Cathedral. He left the small community in Finch’s Buildings to take the appointment of Domestic Chaplain to Mr J. Wheble, who built a commodious house for him within easy reach of his own mansion, where the Abbé said Mass every morning in the handsome Chapel and performed the services on the Sundays for the family, some of the tenantry and neighbouring poor, the number of Catholics increasing under his pious ministry, which he carried on, till the foundation of the Church on the site of the ruins of Reading Abbey, an event which for years he had ardently desired; he then retired to Rouen to close his priestly career where it had begun, bequeathing, when called to his reward, his own chalice to the Church of St James, for which, when he had purchased it, he intended this memorial.

2. My Aunt Elizabeth Anne was married to the Chevalier Le Noir - a French émigré; she was the youngest (sic) of the two daughters of Christopher Smart and inheritor of the purest vein of his poetic genius.

Finis

COMMENT* As Scantlebury points out, in The Catholic Registers of Reading, the date of 1752 is inaccurate as Anna Maria only married Christopher Smart in 1752 or 1853, subsequently living in London and the Ireland before returning to England and Reading. See also Devlin (Poor Kit Smart p65) who argues the marriage date must be 1752 as the marriage had to precede the Hardwicke Act (1753) which obliged all marriages to be registered by an Anglican clergyman. Mrs Smart was widowed in 1771. She most probably returned to Reading in 1762 to take over the Reading Mercury, which changed its name to the Reading Mercury and Oxford Gazette in 1767.

For a detailed account of the history of the Reading Mercury see K G Burton, 'The Early Newspaper Press in Berkshire (1723-1855)', Reading 1954. This also shows that Mrs Smart came to Reading to take over the running of the Reading Mercury in 1762.

******************************************************************

FRANCOIS LONGUET'S LIBRARY AT THE CHAPEL OF THE RESURRECTION

CATALOGUE OF BOOKS AT THE CHAPEL IN READING

This list is to be found in a letter in the Westmister Archives, Poynter Box. Following Longuet's murder a complete inventory of

the house and its contects was compiled. This was probably due to the fact that Longuet's French relatives made claims against the estate and Bishop Poynter thought it wise to have a precise

list.

Genitive apostrophes are missing in original.

Editor’s additions in blue.

Catechism of Christian Doctrine in (?) Latin Folio

Blyths Sermons 4 Vols

Archers Sermons 4 Vols

Do do Second Series 3 Vols

James Archer Sermons, MSS 006, Archives and Manuscripts Dept., Pitts Theology Library, Emory University.

Biographical Note

James Archer was born in London, England to Peter and Bridget Lahey Archer on 17 November 1751. He was employed in a Public House called the Ship where English Catholics fearing persecution met secretly to worship. Discovered there by Bishop Richard Challoner, he was sent to study at Douai in 1769. Archer was ordained and in 1770 returned to London where he was appointed Vicar-general. Renowned for his oratorical skill, he was considered the most popular Roman Catholic priest of his time. Several editions of his sermons were published between 1788 and 1832 and reprinted after his death. He wrote widely on a variety of topics including religious persecution, marriage, spirituality and the religious profession. In recognition of his achievements the Pope granted him a Doctor of Divinity degree. James Archer died on August 1832 at the age of 82 just as a new era of religious tolerance was dawning.

Scope and Content Note

The collection consists of 82 sermons written for Sundays, religious holidays and as inducements into the religious profession. Only one sermon is dated (1788) although the watermarks on the paper run as late as 1826. The sermons are of varying length but generally run to about 12 pages long. The text of the sermons contains many corrections and revisions and they appear to be intended for delivery rather than for publication. He wrote sermons on various Moral and Religious Subjects for All the Sundays and some of the Principal Festivals of the Year, London, 1817. The sermons the style and content of a popular English Catholic priest during the period of Roman Catholic persecution in England.

Appletons Discourses

Discourses on the Grounds of Christian Belief by (?) J H

Butlers Discourses 3 Vols

(Ed Note: This is presumably a work by Bishop Alban Butler cf biographies and author of The lives of the Saints also in Longuet’s library, see below)

Bossuet's Variations 2 Vols

(http://www.nndb.com/people/783/000094501/)

Bossuet was plunged at once into the thick of controversy; for nearly half Metz was Protestant, and Bossuet's first appearance in print was a refutation of the Huguenot pastor Paul Ferry (1655). To reconcile the Protestants with the Roman Church became the great object of his dreams; and for this purpose he began to train himself carefully for the pulpit.

Finally in 1688 appeared his great Histoire des variations des églises protestantes, perhaps the most brilliant of all his works. Few writers could have made the Justification controversy interesting or even intelligible. His argument is simple enough. Without rules an organized society cannot hold together, and rules require an authorized interpreter. The Protestant churches had thrown over this interpreter; and Bossuet had small trouble in showing that, the longer they lived, the more they varied on increasingly important points. For the moment the Protestants were pulverized; but before long they began to ask whether variation was necessarily so great an evil.

Between 1691 and 1701 Bossuet corresponded with Gottfried Leibniz with a view to reunion, but negotiations broke down precisely at this point. Individual Roman doctrines Leibniz thought his countrymen might accept, but he flatly refused to guarantee that they would necessarily believe tomorrow what they believe today. "We prefer", he said, "a church eternally variable and for ever moving forwards."

Chaloners Meditation 2 Vols

Butlers Lives of the Saints 10 Vols

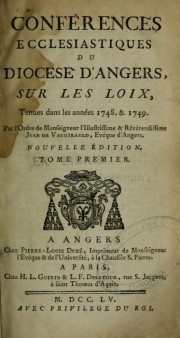

Conferences d'Angers 25 Vols new

Ed note; website: http://www.archive.org/details/cconfrenceseccl00ange

read online

Full title is Conférences ecclésiastiques du Diocèse d'Angers : sur les loix ; tenues dans les années 1748 & 1749

Mannings Truths 2 Vols

Doctrine of the Catholic Church translated into English from Bossuet.

Hays Sincere Christian 2 Vols

Hays Devout Christian 2 Vols

See the following websites:

http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=hay%20devout

For a biogrsphy of George Hay: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Hay_%28bishop%29

Gobinets Instruction for Youth

Charles Gobinet: French theologian born at Saint-Quentin in 1613, died in Paris in 1690. Having graduated from the Sorbonne he was appointed Principal of the College of Plessis where he stayed for 43 years until he died. He published many works amongst which the main ones are: Instruction of youth in the Christian Life based on the teachings founded on the Holy Scriptures and the writings of the Fathers of the Church.

Reeve's Christian Church 3 Vols

P Bakers Works 4 Vols

Douay Bible 5 Vols

Sacraments Explained by JH

Ten Coomandments Explained Do by Do

Christian Directory by R Parsons

Mannocks Poor Mans Catechism

Pensées Evangeliques pour chaque jour de l'année

(Thoughts from the Gospels for each day of the year)

Pensées Evangeliques pour chaque jour de l’année 2 vols

Pseaumes (sic) de David avec des Notes

(Psalms of David with commentary)

Instructions de la Jeunesse par Gobinet

(Instruction for youth by Gobinet. This is an English translation of the work which Fr Longuet also had in French)

Latin Testament

Latin Theology 6 Vols

Webbes Plain Chant